The challenge: have one blog post each week devoted to a specific ancestor. It could be a story, a biography, a photograph, an outline of a research problem — anything that focuses on one ancestor.

Amy’s 2015 version of this challenge focuses on a different theme each week.

The theme for week 19 is – There’s a Way: What ancestor found a way out of a sticky situation? You might also think of this in terms of transportation or migration.

My 19th ancestor is my great-aunt Guadalupe “Lupe” Maria Robledo (1910-1975 ). According to the dual surname convention used in her country of birth, Mexico, her full name is Guadalupe Maria Robledo Nieto.

This post is really about the way my paternal grandfather’s Mexico-born family came to the U.S. Not so much about a particular ancestor. However, since the blog challenge requires we identify a focus ancestor, and since I have already blogged about my both of my great-grandparents for this same challenge, I had to choose a new ancestor or relative. So I have chosen Aunt Lupe, since she is one of the four immediate family members who immigrated to the U.S., and because her border crossing record was one of the two gems I discovered on Monday.

About Aunt Lupe

I have very vague memories of my great-aunt Lupe. She died when I was a very little girl.

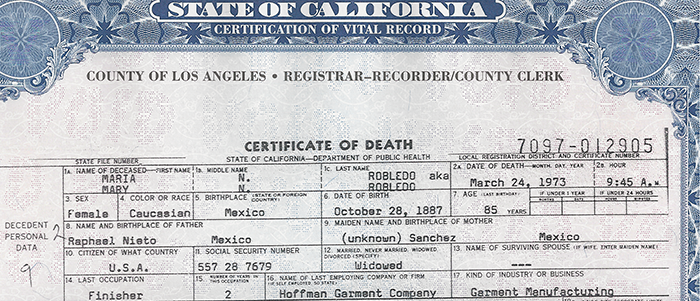

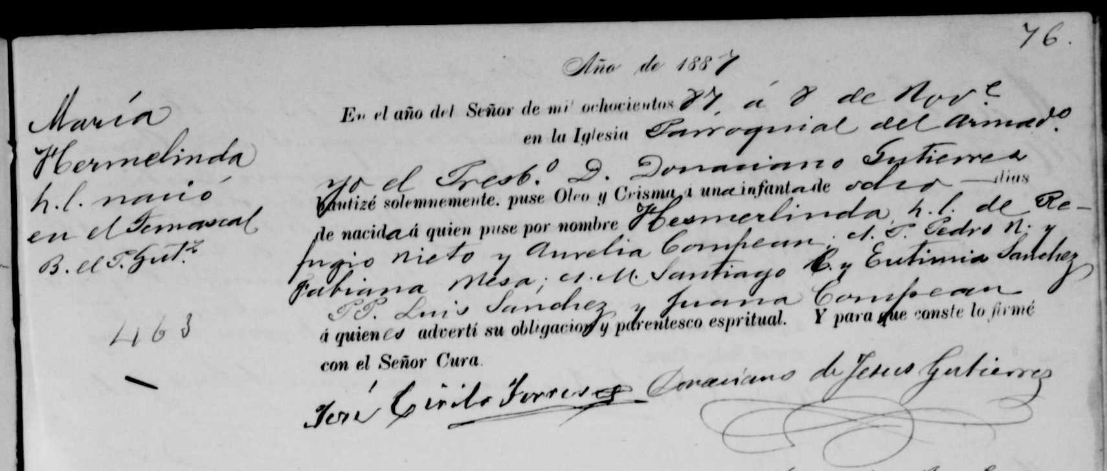

Guadalupe Maria Robledo Nieto was the oldest of eight children born to my great-grandparents, Jose Robledo (1875-1937) and Maria Hermalinda Nieto (1887-1973). She is also one of two children born to Jose and Maria in Mexico; my grandfather Benjamin Robledo (1919-1997) was the first child born in the United States.

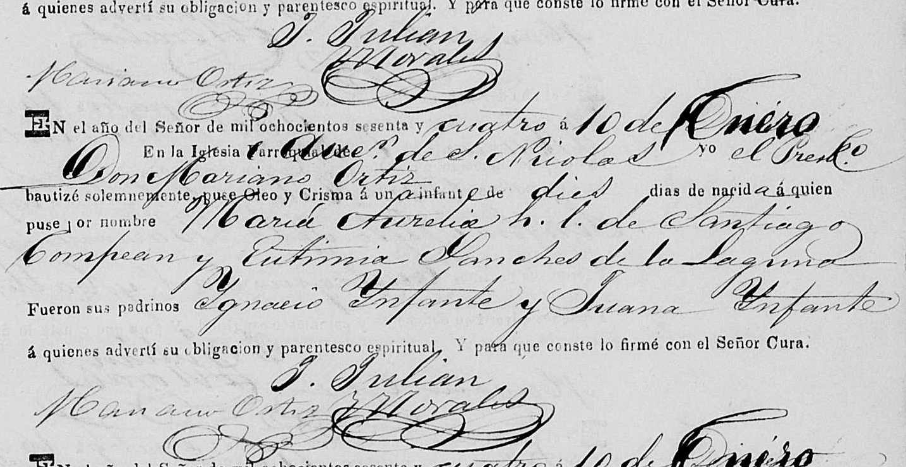

Lupe was born 30 June 1910 in the state of San Luis Potosi, Mexico. I have not yet found a baptism or civil birth registration record from Mexico, confirming the date and place–but it is very likely she was born in the family’s hometown of Tomascal (Temescal) in the municipality of Armadillo de los Infante, state of San Luis Potosi. From what I can tell, she was not given the traditional Mexican order for given names, which would have been Maria Guadalupe, with the saint/biblical name of Maria preceding her primary name of Guadalupe. But since I have not yet found her baptism or civil registration for birth, I can’t be certain of that.

This is all the biographical info I plan to share about Aunt Lupe at this time, because the real focus of this post is on the next major phase of Lupe’s life that I have identified so far–immigrating to the U.S. with her parents and baby brother.

Immigrating to the U.S.

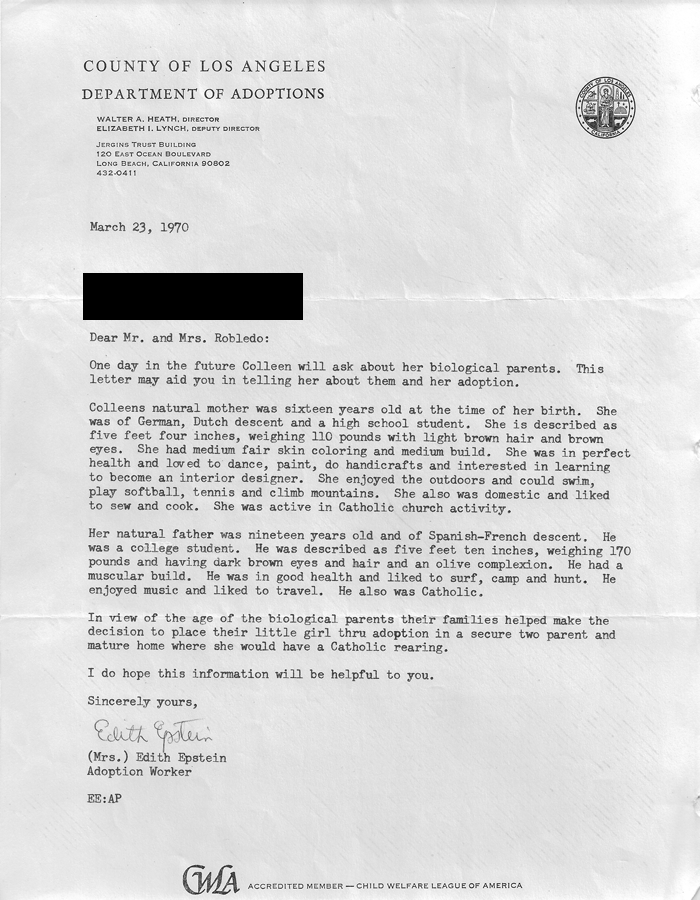

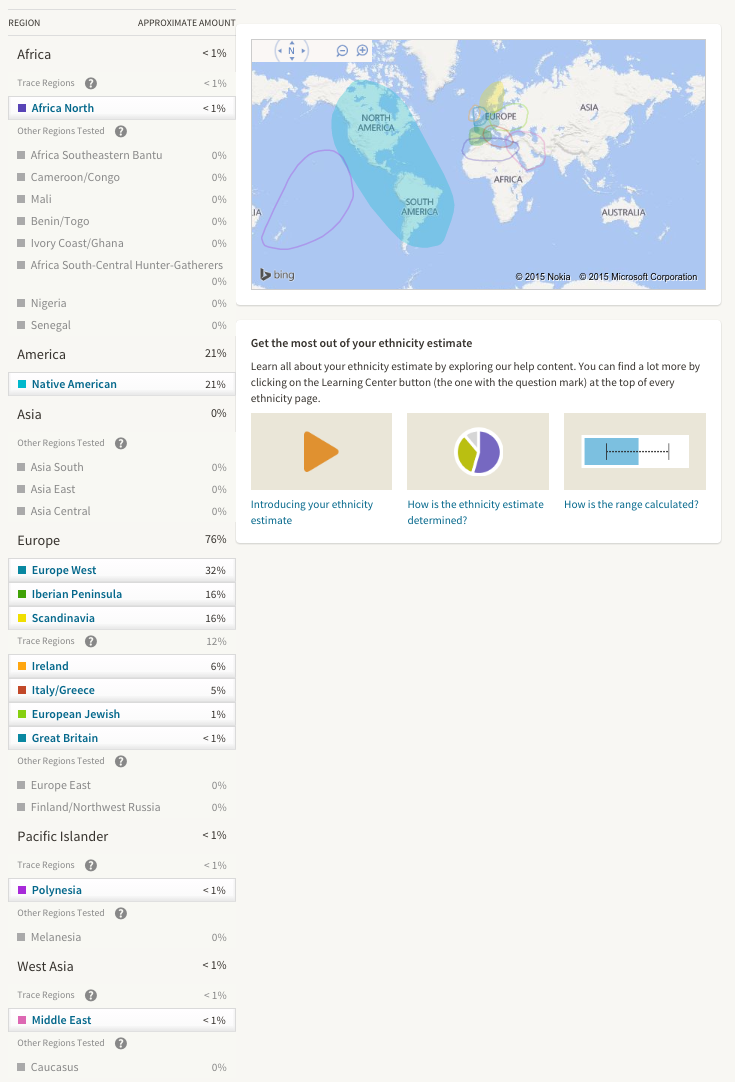

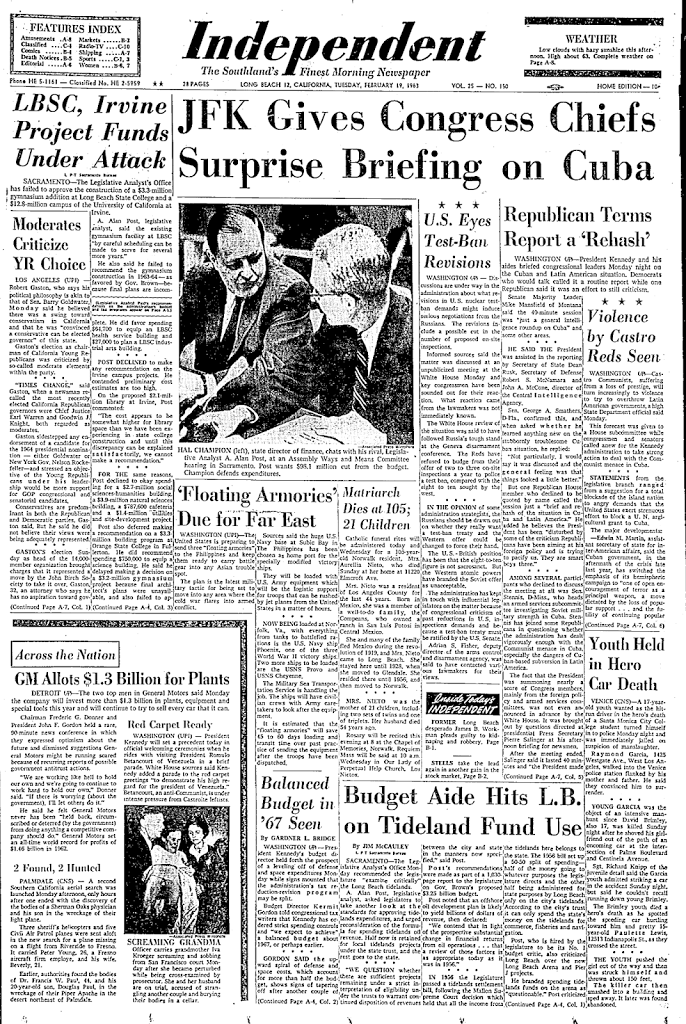

Dad, his cousins, and I have always heard that his father’s family fled to the U.S. to escape the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). The family supposedly had land and lost everything during the revolution. They came seeking a new home, a new life, a fresh start. Much of their extended family immigrated here, in phases, with a large group–that included my great-grandparents–then migrating to Long Beach, Los Angeles County, California.

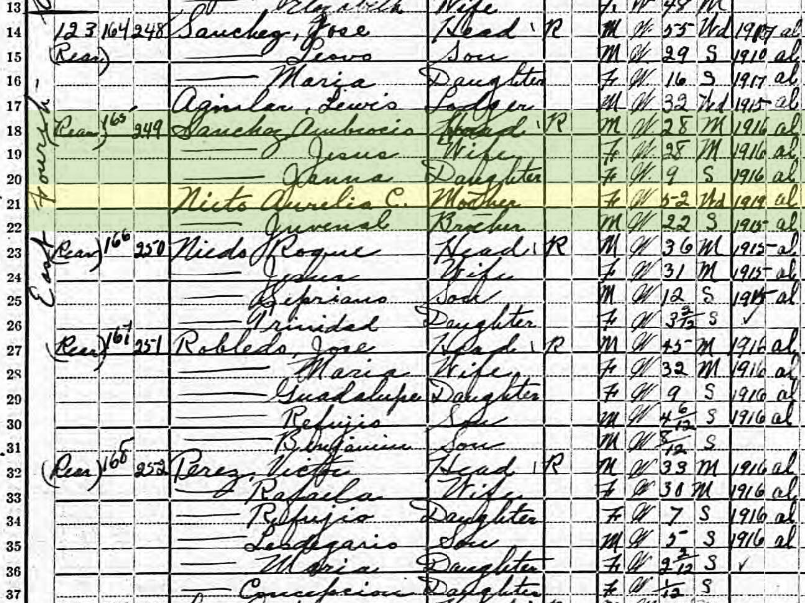

The 1920 U.S. census indicates that the whole immediate family group immigrated in 1916.1 The 1930 U.S. census claims it was 1915.2

For over 15 years, I have tried to find documentation that would identify where and when my grandfather’s immediate family crossed into the U.S. For over 15 years, I have pulled my hair out and banged my head against a wall, each time my attempted search failed.

Two days ago, after 15+ years, the search came to an end.

I found them. All of them. Finally!

Finding Great-Grandmother Maria First

The first documented evidence I came across that indicated the way my grandfather’s family immigrated to the U.S. was the discovery of my great-grandmother Maria “Nana” Nieto’s naturalization records at the National Archives in Laguna Niguel, California, back in 2003-2005 (I didn’t note back then when I found a document). Those documents reference Laredo, Texas, as her point of entry and confirmed entry in October 1915.3 The exact date was noted wrong on those naturalization documents, but I will save that document’s analysis for another post.

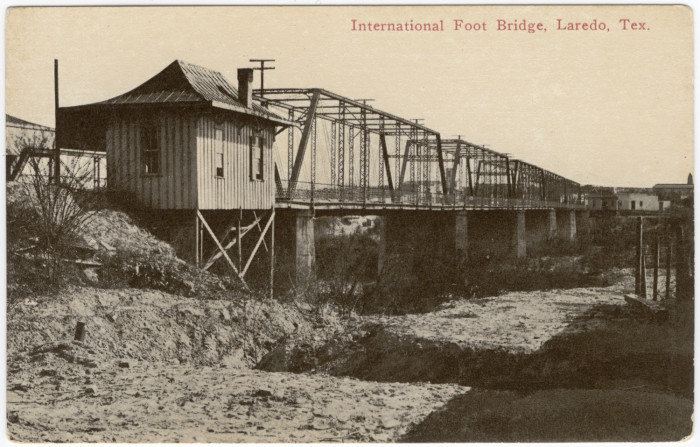

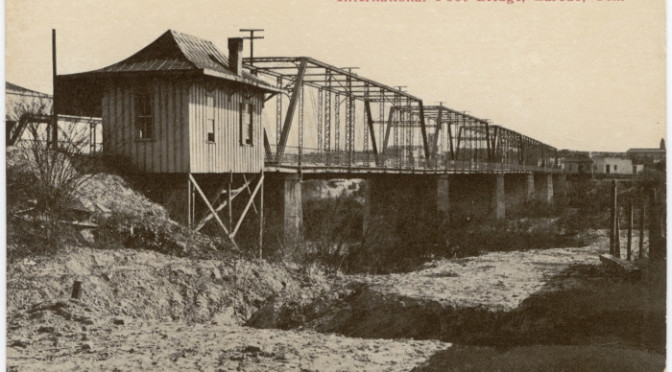

A bit of digging around for information about Laredo, Texas, as a point of entry from Mexico during that era indicated that the Laredo footbridge, over the famous Rio Grande, is how immigrants in 1915 would have entered the U.S. via Laredo. I wrote about the bridge’s history in a 2012 blog post about my great-grandmother Maria’s immigration. According to Wikipedia, the foot bridge (now called the Gateways to the Americas International Bridge) was first constructed in the 1880s, was destroyed by a flood in 1905, then repaired, and was rebuilt in 1932, continuing this cycle through present day.4

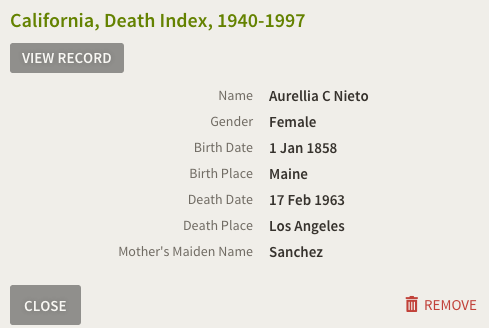

Once Ancestry had the digitized US-Mexico border records indexed, the information on Nana’s naturalization records allowed me to find her border entry record in 2012.

Nana, or Maria, is identified under her paternal surname of Nieto (what we would think of as a maiden name), not under Robledo (what we think of as a married name). Back in 2012, this had me a bit stumped, as to why my great-grandmother was not recorded as Maria Robledo. I did not then fully understand the dual surname convention used in Mexico, and that Mexican women do not take their husband’s name. Mexican immigrant women generally only become identified by their husband’s name after coming to the U.S., on U.S.-generated records, such as a census, city directory, or death record.

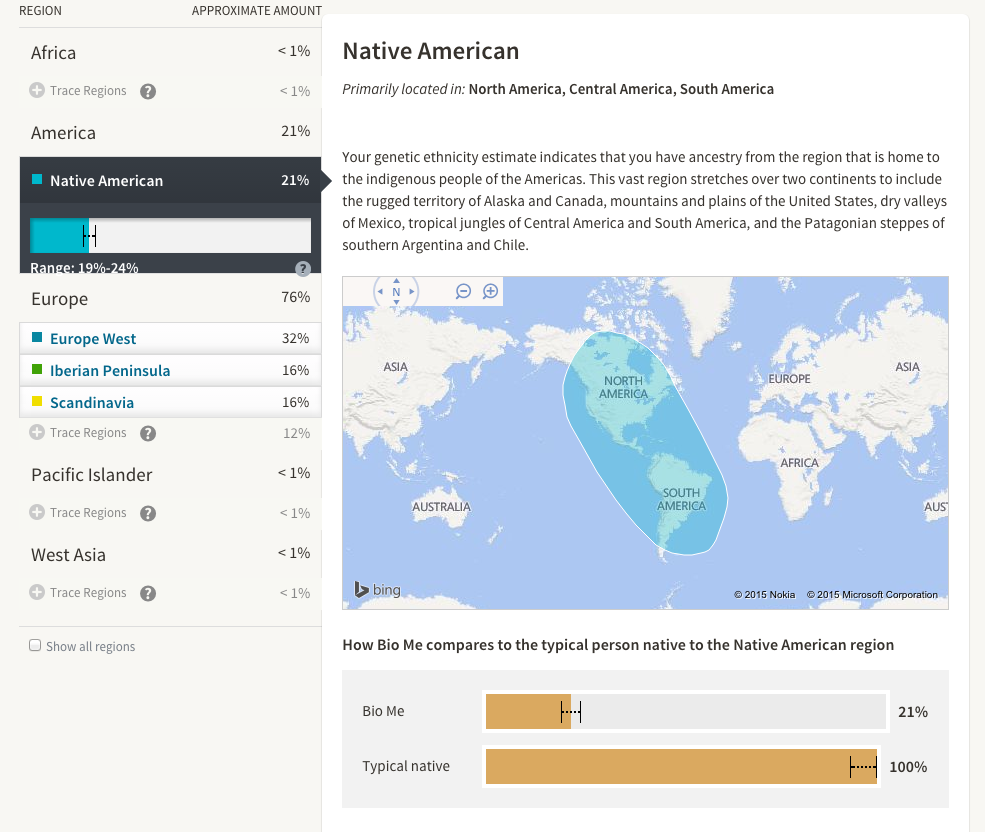

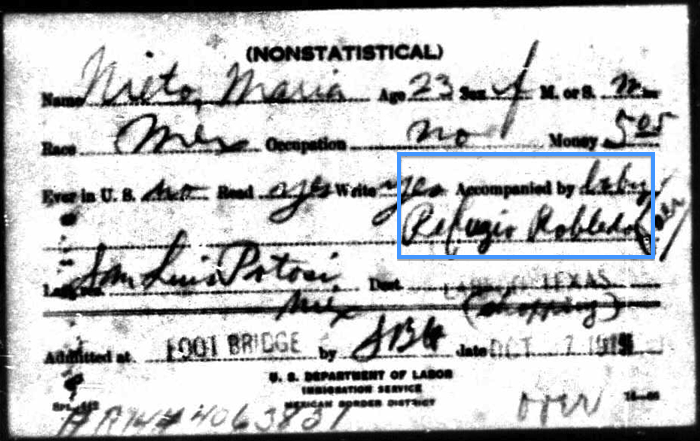

She was admitted via the bridge, on 27 October 1915. The “2” in the date is hard to read on her card, but further evidence confirms the 27th as the date.

[contentblock id=3 img=html.png]

Maria’s border entry card indicates that she was married, that she was accompanied by “baby Refugio Robledo,” and she was entering the country for “shopping.”5

Baby Refugio Robledo

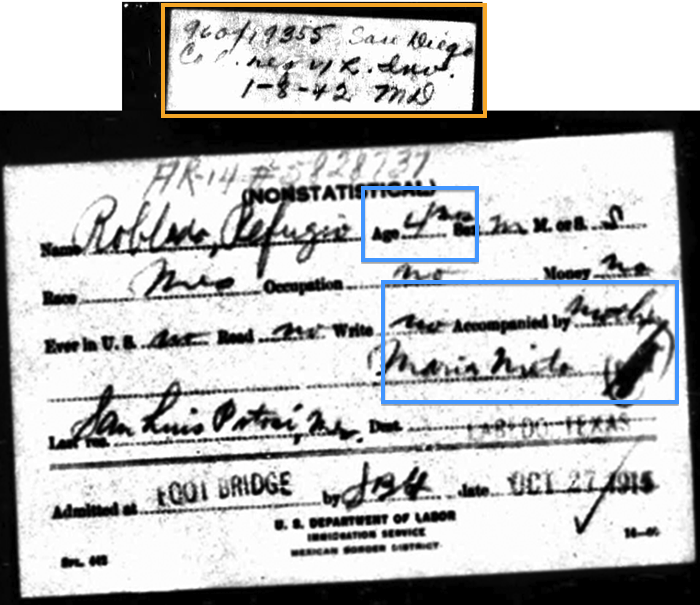

That four-month-old was my great-uncle Refugio Raphael “Ray” Robledo (1915-?).

Note that Refugio’s border entry card more clearly indicates the date that he and his mother Maria entered the U.S.–October 27th. 6

Nana had two children by this time, including older daughter Guadalupe. So why wasn’t Maria accompanied by Lupe as well? Why not also accompanied by her husband, my great-grandfather Jose? Why was the family split up at the border? Where were Jose and Lupe?

If the family had been split up, for whatever reason, one can reasonably assume why an infant is the child who would be left with the mother. Maria would have been nursing baby Refugio; not exactly something her husband Jose could do.

[contentblock id=4 img=html.png]

Discovering Great-Grandfather in an Old Clue

Two years after finding the border entry cards for Maria and her baby son Refugio, I still had not been able to find out what happened to older daughter Lupe and husband Jose Robledo.

Until this past Monday.

Thinking that I might focus this blog post topic on Baby Refugio’s way into the U.S., I took another look at the border records for both Refugio and his mother Maria Nieto. Nothing. No Jose Robledo or Guadalupe Robledo with the right birth and family info anywhere. I looked at EVERY person recorded as crossing on that same date. Also for the date before, and the date after. I looked at every Robledo and Nieto who crossed in October 1915. Still nothing.

But…then…there…it…was…staring me right in the face.

The whole time.

I just hadn’t ever registered and thought-out the note before. Perhaps because it never even meant anything to me, until a month ago.

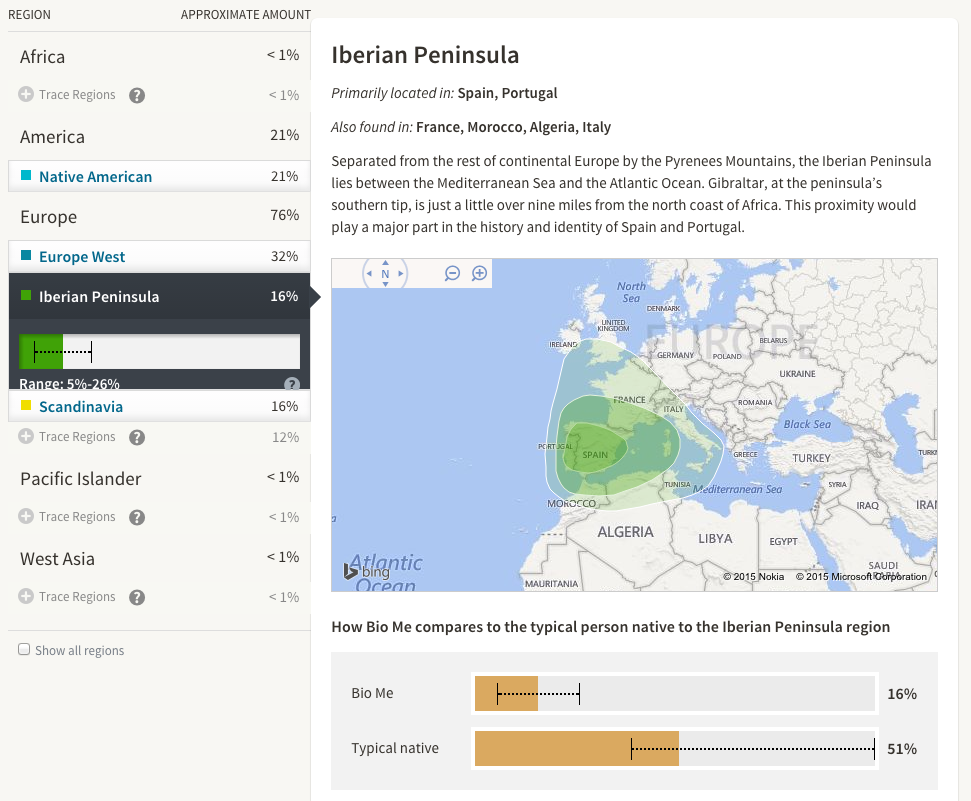

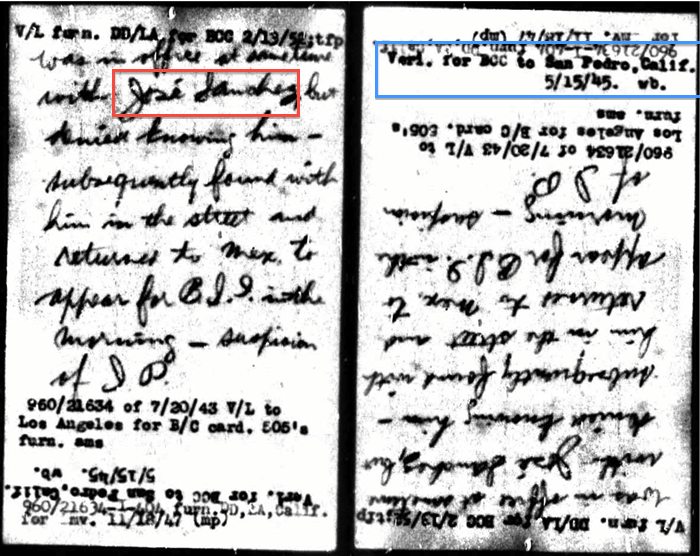

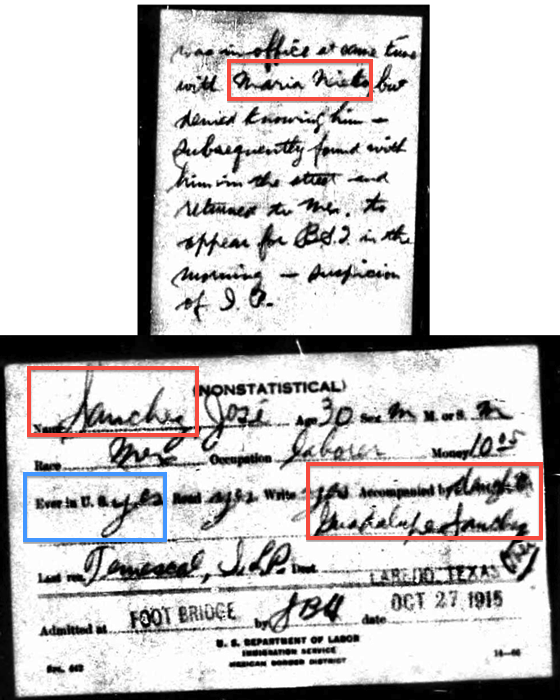

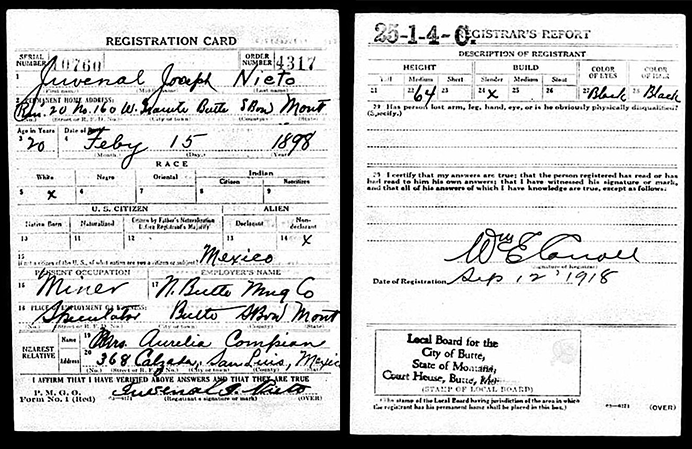

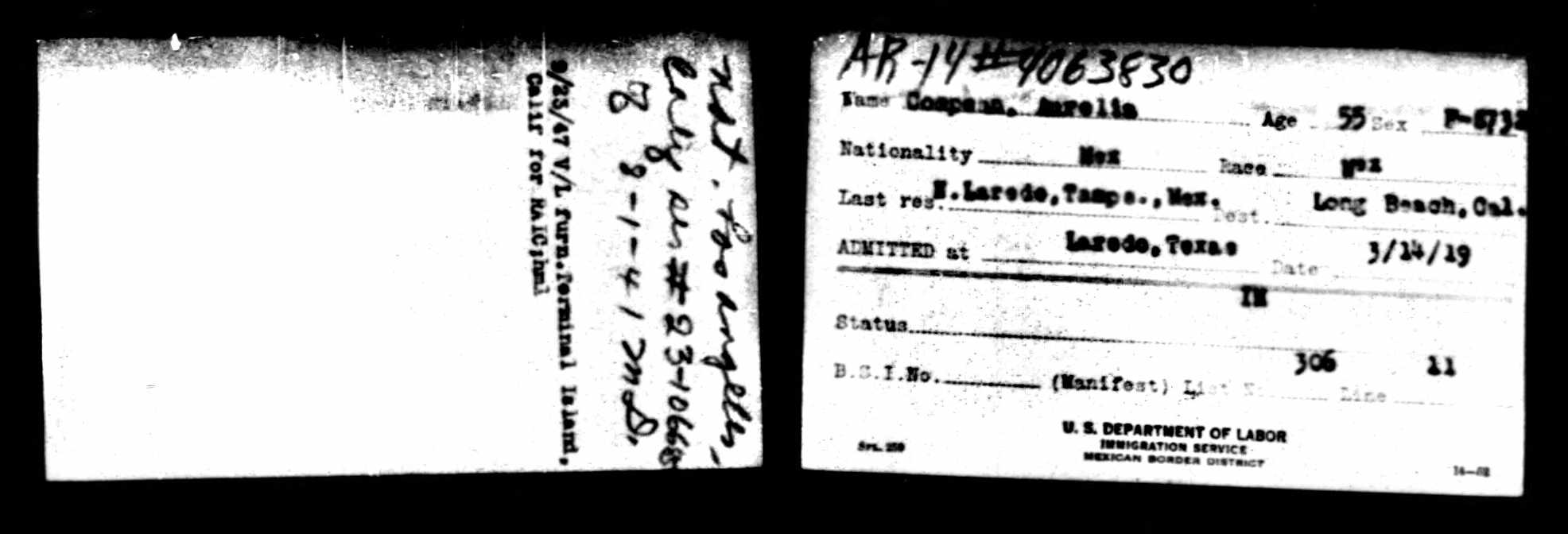

The back of Maria’s border entry card has a handwritten note about her being caught with a Jose Sanchez.7

Was in office at same time with Jose Sanchez but denied knowing him — subsequently found with him in the street and returned to Mex to appear for B.__.__. in the morning — suspicion of __.

I had seen that note many many times, and dismissed it every time.

The name Jose Sanchez meant nothing to me. I had no such person in my database. Jose Sanchez must have been a stranger, someone she ran into at the border. But, then, why was she later seen with him again on the streets? Was she so scared after being detained in a strange new country, that she gravitated towards the only other person there she knew–the person she had met in the immigration office?

This time, it clicked.

Sanchez.

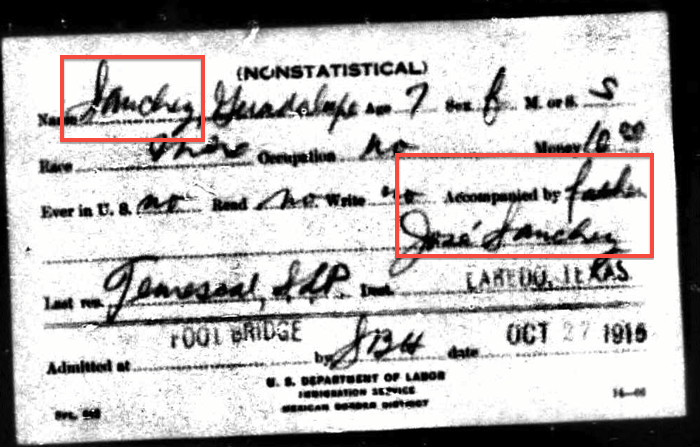

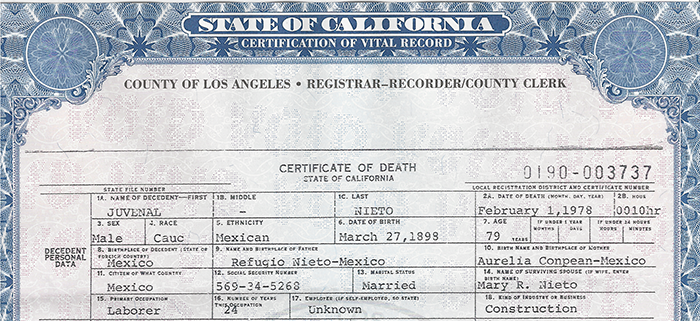

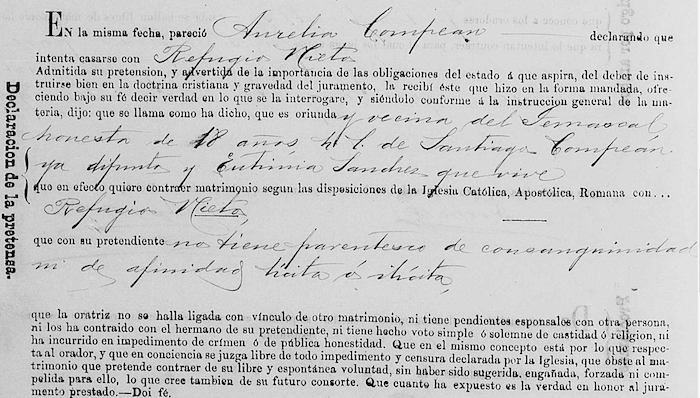

My great-grandfather Jose Robledo’s maternal surname is Sanchez. According to Mexican naming conventions (those darn dual-surnames again!), his full name is Jose Robledo Sanchez [a 2nd given name has not been found for him]. Until last month, I did not even know that. Because last month, another 15+ year brick wall was finally busted, when I found Mexico Catholic parish records identifying my great-grandfather’s parents’ names–which no currently living member of our family ever knew. Until my discovery last month.

Either Jose intentionally misled border officials by giving them his maternal surname as his only surname, or, as is so often the case with Mexican immigrants, U.S. officials (not understanding the dual-surname convention) recorded the maternal (last) surname as the lone surname.

I had seen and dismissed a 27 October 1915 border entry record for a Jose Sanchez. Stupid mistake. Especially considering the note about a Jose Sanchez on the back of Maria’s record.

BINGO!

That border record for Jose Sanchez matched the birth info for my great-grandfather and noted that he was accompanied by a daughter named Guadalupe! Even better…like Maria’s card, Jose’s border entry card contains an identical handwritten note on the back–indicating that he was detained and caught with a Maria Nieto.8 My Maria Nieto! His Maria Nieto!

At long last…my great-grandparents. Identified together. Detained together. Later caught again together. And hopefully, allowed to cross together.

The record for this Jose Sanchez, my great-grandfather, indicates that he was accompanied by his daughter Guadalupe.

And Guadalupe Makes Four!

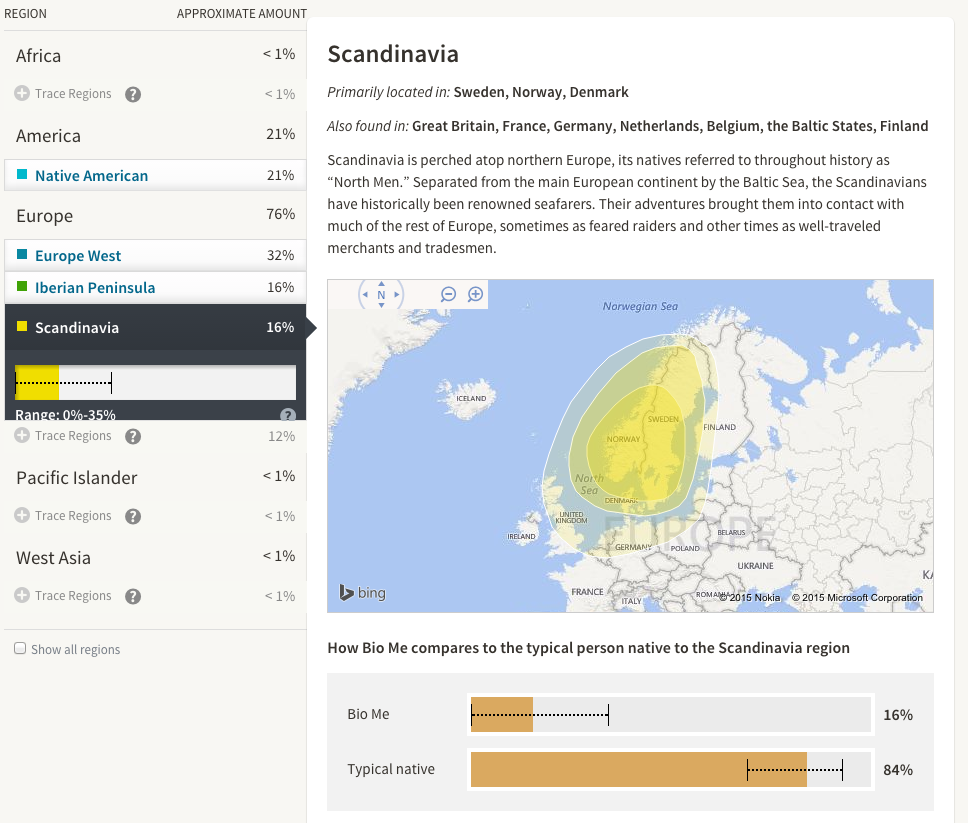

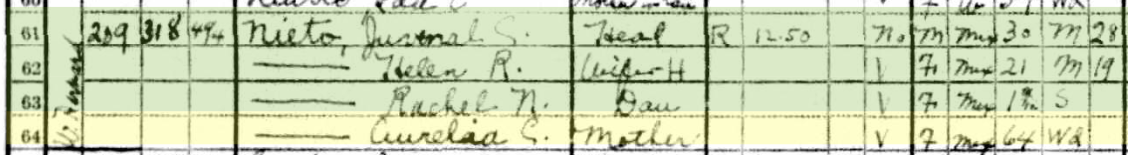

This discovery allowed me to quickly find the last border crossing record, for Aunt Lupe.

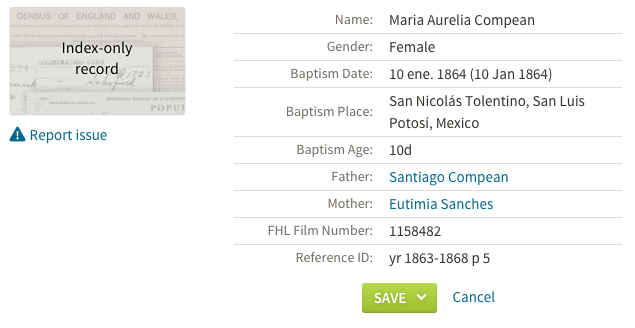

Guadalupe Sanchez [Robledo] is recorded as 7 years old (we think she was only 5 years old), from the right hometown, accompanied by her father Jose Sanchez.9

All four of my paternal grandfather’s immediate family entered the U.S. on 27 October 1915.

But, why is Aunt Lupe recorded with the name Sanchez? Sanchez is not one of her dual-surnames. Her full Mexican name is Maria Guadalupe Robledo Nieto. It is very likely that because her father Jose was recorded under just his second/maternal surname Sanchez (border officials probably thought Robledo was a middle name), officials simply assumed–like U.S. children–that Mexican children inherit a single surname from their father. Hence, Guadalupe Sanchez was born at the border.

Celebrating the 100th Anniversary

While preparing for this blog post theme, and in reviewing these records again over the past couple weeks, I had another significant discovery…if my family immigrated in 1915, then this coming October 27th marks the 100th anniversary of them crossing the border and crossing the Laredo footbridge to their new country.

The 100th anniversary! Coming up this year!

How can one pass up the chance to walk where their ancestors walked, exactly 100 years ago?! To stand where their ancestors stood exactly one century prior, staring across the Rio Grande, taking that walk (and leap) of hope, into a new country?

This gal ain’t passing up that chance!

I’m headed to Laredo, Texas, this fall, to walk across (not drive across) the international bridge into the border town of Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, then back across the Rio Grande again into the United States. The way my great-grandparents and their two oldest children did it. The actual bridge from 1915 no longer stands. It’s a newer bridge. So it won’t be in their exact footsteps, but it’s as close as I can get to retracing their steps. And best of all, I’m taking Dad with me! He was raised by my great-grandmother Maria Neto, his grandmother. She was the only mother he ever really had. I can’t wait to stand on that bridge with him, sharing this emotional experience, as we both reflect upon what all that Laredo bridge symbolizes for our family.

Follow-up Questions

Finding these final two border crossing records answered some key questions about the Mexico-born members of my paternal grandfather’s immediate family, but it also raises many more, to which I will most likely never get answers.

- Why were my great-grandparents detained in a government office?

- Why did they deny knowing each other when questioned in that office?

- If they were in the same office, pretending not to know each other, how on earth did they keep little Lupe from crying out and running to her mother, giving the cover story away?

- Were they indeed returned to Mexico, for further questioning the next day?

- So would that make their official immigration date the day after October 27th…the 28th?

- What sort of questioning took place the next day, and are there records?

- What prompted officials to release them and allow them to continue on their journey?

My heart breaks for the terror they must have experienced. The fear that must have forced Maria and her husband Jose to deny knowing each other, perhaps thinking it might protect the other person–allowing the other spouse and at least one child safe passage if one set were detained or sent back. The fear that they might be sent back, all journey preparations for naught, returned to a war-torn country. The fear that their family might be separated…across a border, in separate countries.

What admiration I have for these two people, who lost everything, faced this fearful situation, and persevered. Persevered to make a new home for their young family, to grow their family with more children, and to instill such a profound sense of family and love among generations of children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and now 2nd great-grandchildren. Maria and Jose were always poor here, but they left a very rich legacy.

Lessons Learned

Having missed the final two border entry cards multiple times over the past two years has taught me some valuable lessons.

- ALWAYS look for records and references to Mexican immigrants under both of their conventional surnames.

- ALWAYS look for records and reference to Mexican immigrants’ children under any combination of the parents’ dual surnames (all four surnames).

- ALWAYS pay close attention to, and frequently re-visit, notes written on the back of or in the margins of records.

My last two blog posts focused on my 2nd great-grandmother

My last two blog posts focused on my 2nd great-grandmother

My 15th entry in Amy Johnson Crow’s “

My 15th entry in Amy Johnson Crow’s “