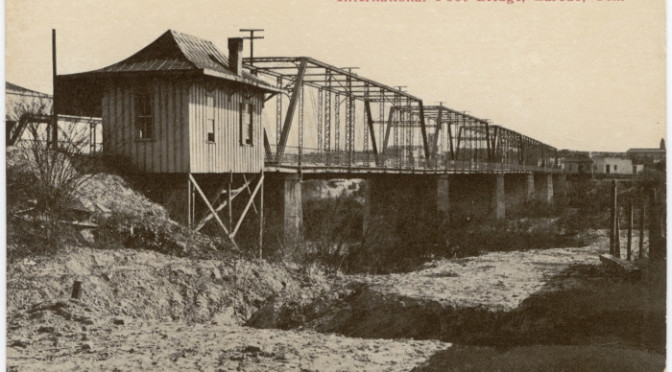

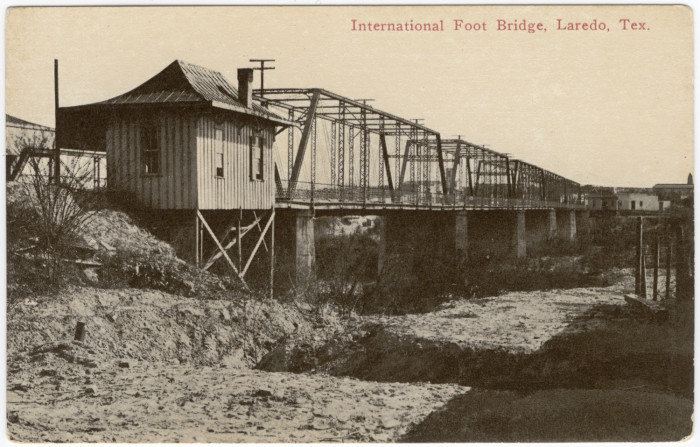

That breakthrough has prompted me to try to uncover another immigration mystery that has plagued me for a good decade…with whom did my 2nd great grandmother, Maria Aurealia Compean (1864-1963)–Maria Hermalinda’s mother–cross when she entered this country from that same Laredo, Texas footbridge?

About Maria Aurelia Compean

My 2nd great grandmother Maria Aurelia Compean Sanches–using the traditional Mexican dual surname convention–was born on 01 January 1864 in a municipality of the state of San Luis Potosí, Mexico.2 She went by the name Aurelia, but our extended family refers to her as “Little Grandma.”

My 2nd great grandmother Maria Aurelia Compean Sanches–using the traditional Mexican dual surname convention–was born on 01 January 1864 in a municipality of the state of San Luis Potosí, Mexico.2 She went by the name Aurelia, but our extended family refers to her as “Little Grandma.”

Aurelia married my 2nd great grandfather Refugio Nieto (1863-1909) on 18 October 1883 in Villa de Yturbide (now Villa de Hidalgo), another municipality in San Luis Potosí, Mexico.3 Family says that her husband Refugio died in 1909. Little Grandma’s obituary claims she gave birth to 21 children, but I have only been able to account for 5 of them thus far.4

Aurelia, along with at least several of her grown children and their families, immigrated to the United States, fleeing the Mexican Revolution after losing their land.5 Aurelia lived at different times with several of these children in Los Angeles County, California, spending her latter years with daughter Maria Hermalinda–my great-grandmother–as well as my father, who was raised by his grandmother Maria Hermalinda.

[contentblock id=5 img=html.png]

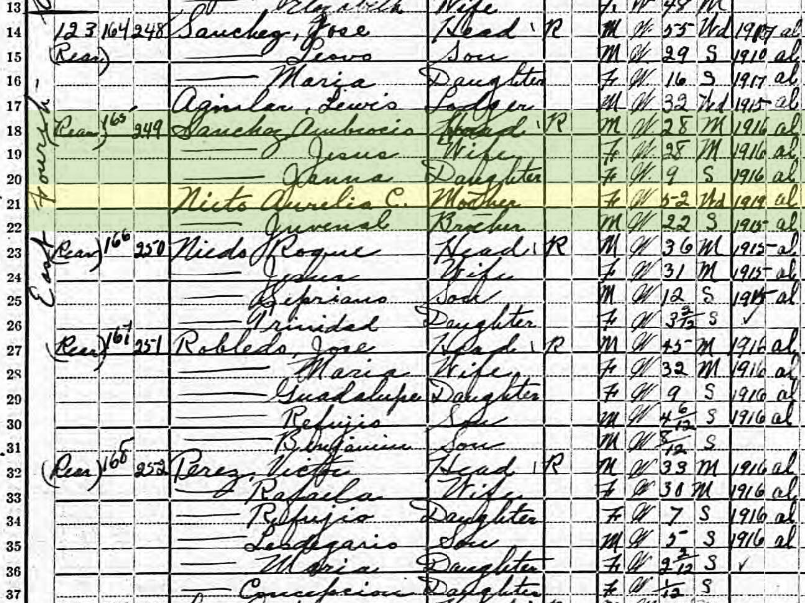

Immigrating to the U.S.

The 1920 U.S. census indicates that Aurelia immigrated in 1919.6 This same census notes that her daughter Maria Hermalinda, along with Maria Hermalinda’s husband and two oldest children, immigrated in 1916 (it was actually 1915).7 This census, which enumerates what I think is a large extended family group together, shows different years for the other members of Aurelia’s family–she is the only person noted as immigrating in 1919.8 9 10 11 12

Taking a look again at Aurelia’s 1963 obituary, it too notes that she came to the U.S. in 1919. But other than indicating, “She and many of the family fled Mexico during the Revolution of 1919, and Mrs. Nieto [her husband’s surname] came to Long Beach.” the obit does not indicate specifics about the family members with whom she immigrated.13

At 55 years of age when she crossed over that border, there is just no way that my dad’s family would have allowed non-English-speaking Little Grandma to immigrate all by herself, and then make the trek to California alone. But with whom did Little Grandma immigrate?

I would think that she entered and traveled with one of the family members with whom she first lived in the U.S.–that big extended family group on the 1920 census. It makes sense that a person or persons with whom she would live here would escort her the entire way, from her central Mexico home village to the Laredo border entry, then across Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and finally California to her new home in Long Beach.

Yet no one on that 1920 census group shares her 1919 immigration year.

Immigration year…

The 1920 U.S. census asks in what year a person immigrated to the U.S.14 Not in what year a person last entered the U.S. A person could officially immigrate (with the intention to stay), yet continue traveling between the two countries. So it is very likely that someone from that big 1920 census extended family group did escort Little Grandma in 1919; the census simply notes their official immigration date, not dates of any additional border crossings since that official immigration date.

Revisiting Her Border Record

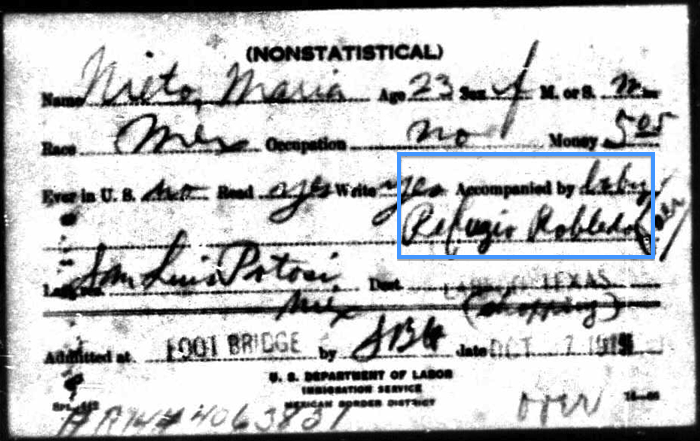

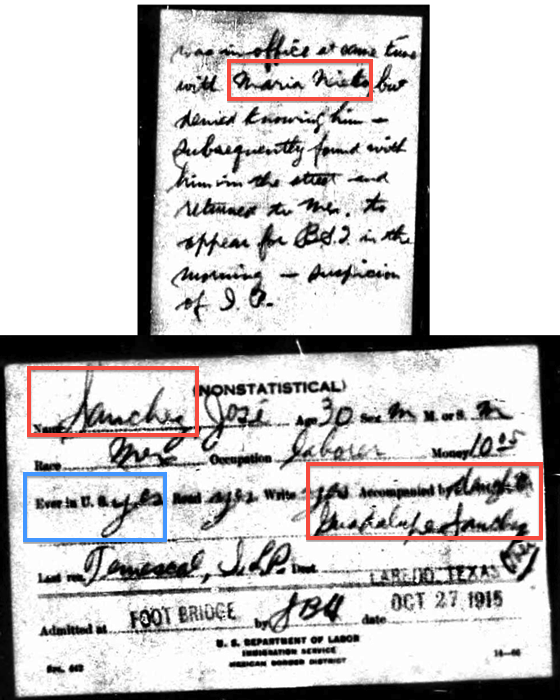

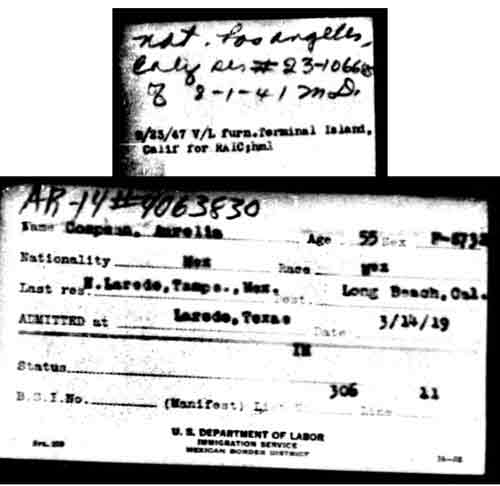

Aurelia did indeed immigrate into the U.S. in 1919–on 14 March 1919, to be exact. But there is no notation of her traveling with anyone.15

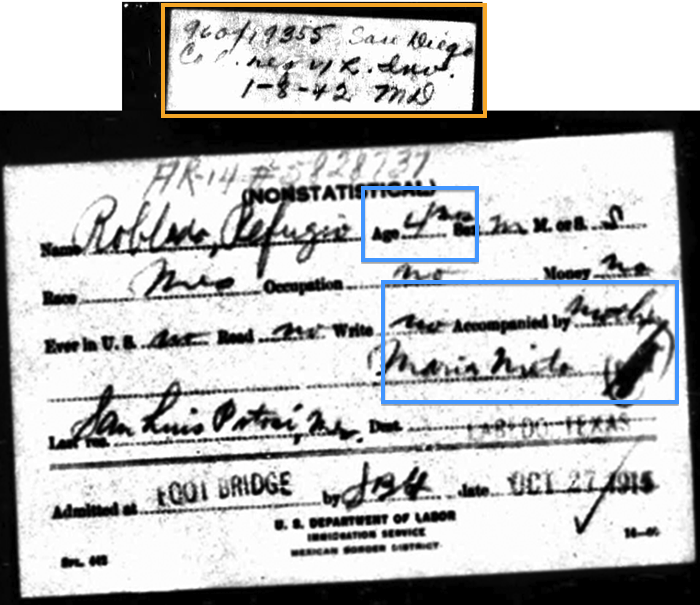

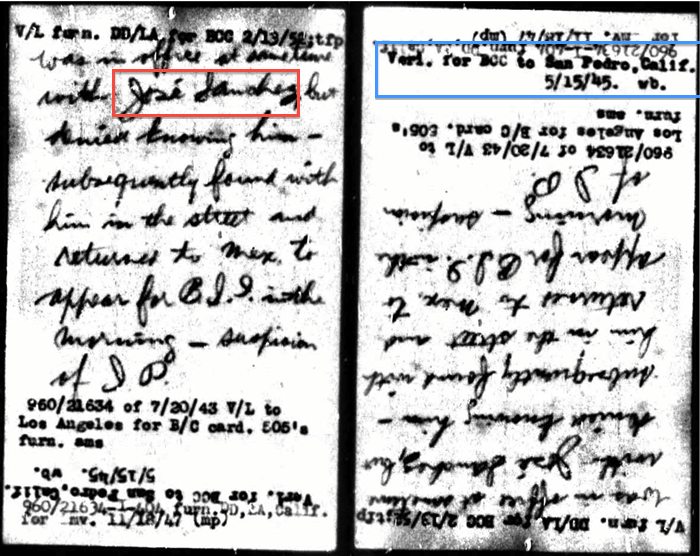

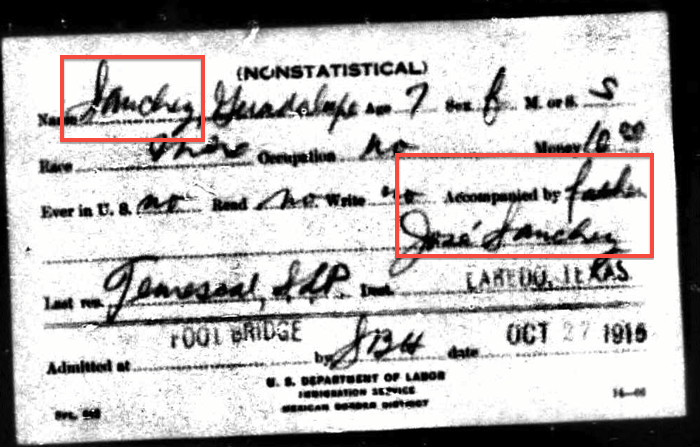

Little Grandma is recorded as Aurelia Compana on the border entry card; it should be Aurelia Compean. It is interesting to note that she is identified with just her paternal surname of Compean. This is consistent with how her daughter (my great grandmother) was recorded–as Maria Nieto, under her paternal surname.16 Aurelia’s son-in-law (my great grandfather, Maria’s husband), however, was recorded under just his maternal surname as Jose Sanchez, which is what made it so difficult for me to track down my great grandfather’s border record. I spent over a decade looking for his border entry record, complicated by not knowing his mother’s name until this month.17 When asked her name, if Little Grandma had answered according to Mexican tradition, she would have provided the name Aurelia Compean Sanches. Yet border officials did not record her surname as Sanches.5

RESEARCH TIP: Mexican Surnames & Immigration Records

When looking for individuals among these Mexican border crossing records, it is often necessary to search for them under all applicable surnames: just the paternal surname, just the maternal surname, and the traditional dual surname. I even advise that for married or widowed women, you check for them under their husband’s surnames using this same approach. Although women in Mexico do not legally take their husband’s name upon marriage, those who immigrated to the U.S. might be mistakenly recorded under their husband’s name, as per traditional U.S. naming customs. It is not unusual to find one of the surnames (usually the paternal surname, because it comes first in the dual surname order) listed as a middle name.

Also very interesting is that Aurelia’s border card notes N. Laredo [Nuevo Laredo], in the state of Tampe [Tamaulipas], Mexico, as her last residence.19 Not the municipality in the state of San Luis Potosí, Mexico, in which she lived her entire life! Had Little Grandma been detained on the Mexican side of the border when trying to immigrate back in 1915, 1916, or 1917 with other family members. Or had she voluntarily moved and stayed there (perhaps with another child?), while her extended family continued on to their new home and country, thinking there was nothing left for her back in San Luis Potosí? Perhaps the revolution quickly escalated in her home area in 1919, forcing Aurelia to flee sooner than the prearranged date on which one of her Long Beach family members was scheduled to go back to San Luis Potsí to escort her the entire way, requiring her to set up temporary residence on the Mexico side of the Laredo border point until that family member could get to her at the border.

Although the back of her border entry card has notations that seem to indicate she naturalized, my family does not think that Little Grandma ever became a U.S. citizen, and I have not yet found naturalization records for her.

California-Bound

As previously mentioned, and noted in the 1920 U.S. census, several of Aurelia’s grown children had already immigrated in 1915, 1916, and 1917 and were living in Long Beach, Los Angeles County, California.

Her border card indicates that Aurelia immigrated with Long Beach, California, specified as her intended destination. Ten months after immigrating via the Laredo border entry point, Aurelia is living with her extended family in Long Beach when enumerated on 10 January 1920.

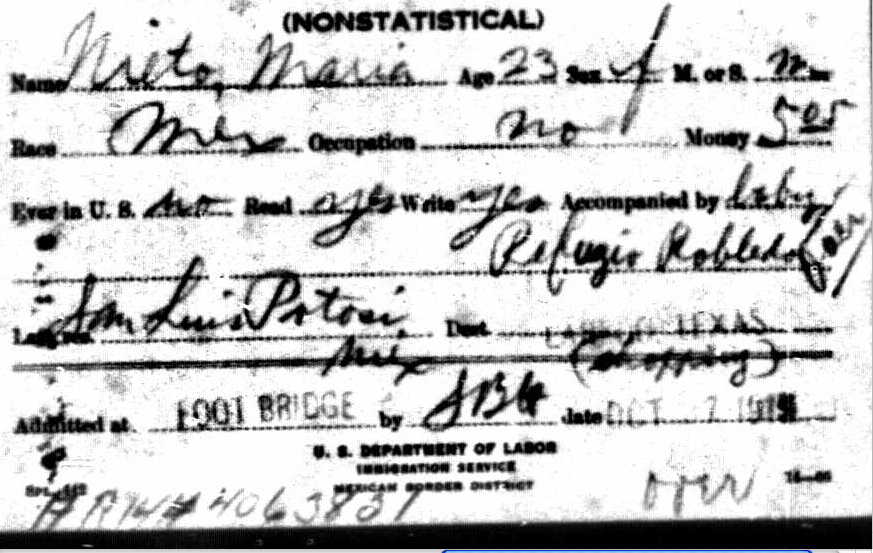

Same-Date Crossings

Because this technique helped me to finally identify my great-grandfather’s border crossing record, I decided to peruse the names of everyone who is indexed as having crossed at Laredo on the same date as Aurelia Compean. Ancestry’s “Border Crossings: From Mexico to U.S., 1895-1964” index retrieves records for 132 others who crossed on 14 March 1919. I find no one else identified with the surname Compean, with her married name Nieto, or with her maternal surname Sanches. I find one Robledo, an Adolfa, whom I do not recognize, also with a last residence in Nuevo Laredo, but listed as traveling alone.22 I find no one else identified from the state of San Luis Potosí, Mexico.

So I will have to investigate Adolfa Robledo a bit more, and start going through all 131 additional records for clues that might help me identify a possible unknown family member from the same area of Mexico where Aurelia’s family lived.

Although as previously discussed, it may simply be that one of Aurelia’s Long Beach family members traveled back to Mexico to accompany Little Grandma across the border and to California–in which case, a 14 March 1919 border entry record would not have been created for them. However, I might find that 14 March 1919 date noted on the back of an earlier border entry card that would have been created on that family member’s official immigration date. I have found similar such notations on other border entry cards, tracking additional reentry dates.

Family Immigration Timeline

I have started a timeline to help me keep track of the facts pertaining to my family’s immigration while I continue to piece together this part of their history.

- 27 October 1915: Daughter Maria Hermalinda Nieto, son-in-law Jose Robledo, and their two children Guadalupe and Refugio Robledo immigrate to the U.S. via the Laredo footbridge between Laredo, Texas, and Nuveo Laredo, Mexico.

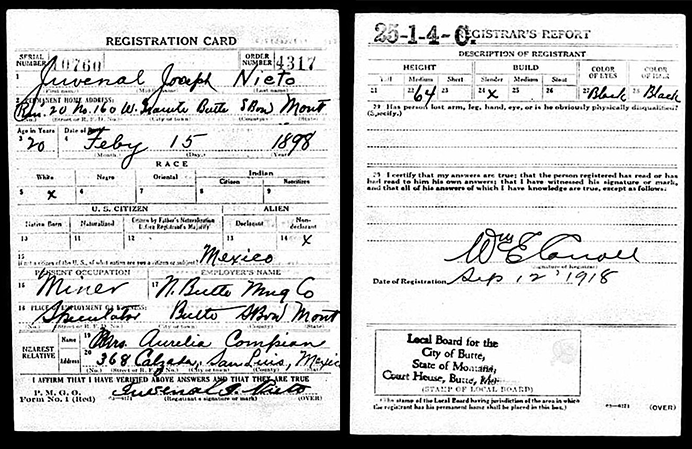

- 12 September 1918: Son Juvenal Joseph Nieto is living and working in Butte, Montana, at the time of the WWI draft. He indicates his mother is still living in [the state of] San Luis [Potosi], Mexico at this time.

- 14 March 1919: Aurelia Compean crosses into the U.S., via the Laredo footbridge.

In addition to reviewing the border records for those other 132 people who crossed the Laredo footbridge the same date as Aurelia, I will have to re-visit that 1920 U.S. census to start tracking and tracing the other extended family members in hopes of finding clues and evidence that help me identify who traveled with Aurelia to her new country and home. I will update this timeline as I uncover more details.