My 25th entry in Amy Johnson Crow’s “52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks” family history blogging challenge for 2015.

The challenge: have one blog post each week devoted to a specific ancestor. It could be a story, a biography, a photograph, an outline of a research problem — anything that focuses on one ancestor.

Amy’s 2015 version of this challenge focuses on a different theme each week.

The theme for week 25 is – The Old Homestead: Have you visited an ancestral home? Do you have photos of an old family house? Do you have homesteading ancestors?

My 25th ancestor is my husband’s 2nd great-grandfather Leonard Jackson Harless (1858-1946).

My 25th ancestor is my husband’s 2nd great-grandfather Leonard Jackson Harless (1858-1946).

About Leonard Jackson

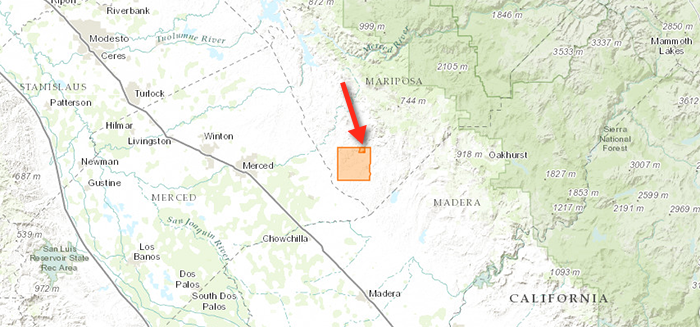

Leonard Jackson was born on the overland journey (possibly in present-day Nebraska or Utah), when his parents emigrated via wagon train from Missouri to California.1 The family crossed from Nevada into California over Ebbett’s Pass, a High Sierras pass that closes during winter each year.2 Last July, my husband and I made a road trip retracing the family’s route from the eastern end of Ebbett’s Pass, following their settlement steps down the western side of the Sierras across the California Central Valley, and then south to Mariposa County.

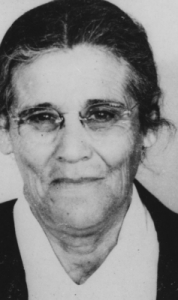

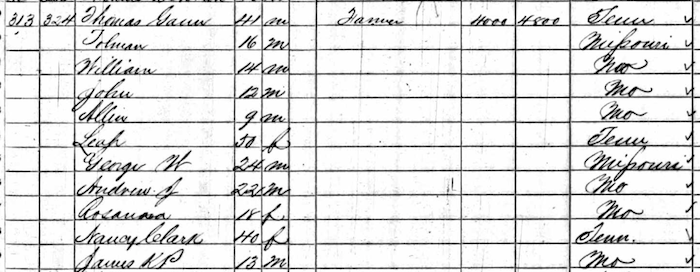

Born to Miles Washington Harless (1826-1891) and Margaret Daisy Gann (1830-1919), Leonard Jackson was third of eight children, and the oldest of two sons. His 3rd great-grandfather was Johan “John” Philip Harless (1716-1772), the progenitor of the large well-established Harless line in the United States. Leonard Jackson married his second cousin Pauline/Paulina “Lena” Adeline Gann (1860-1938) on 26 August 1889 in Merced County, California.3 The couple spent the majority of their married life in Mariposa County, where they are buried side-by-side at the historic Mariposa District Cemetery.4

[contentblock id=21 img=html.png]

Homestead Records

Homesteading played a critical role in the settling of the American West. Yet despite being a Western U.S. historian (specializing in California history), I never paid much attention to homestead records because most my ancestors were late-comers to the U.S. who did not even own homes until the early-to-late 1900s. And homesteading (aka the Homestead Acts) just happened back in the 1860s, right? [Wrong.] Most of my people weren’t even in the U.S. at that time. Nor was it a topic discussed in any detail during my college California history classes, or in my own California history research.

California Homesteading

When I saw a session being offered by Jamie Lee McManus Mayhew at the Southern California Genealogy Jamboree this past June on “Homesteading California,” I thought that the California historian in me ought to go learn a bit about this historical era and its records. The information might come in handy when helping library patrons at work, or helping others with their family history. Even if my California ancestors weren’t homesteaders.

Discovering GLO

During her session, Jamie talked about and demonstrated GLO.

While GLO–in genealogy-speak, the Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office database index and digitized records– was a database I was aware of, I never bothered to actually use the site, since I was certain my ancestors were not homesteaders, and did not think it likely bought any other federal land.

We provide live access to Federal land conveyance records for the Public Land States, including image access to more than five million Federal land title records issued between 1820 and the present. We also have images related to survey plats and field notes, dating back to 1810. Due to organization of documents in the GLO collection, this site does not currently contain every Federal title record issued for the Public Land States.5

Sitting through that introduction to GLO, a thought hit me…

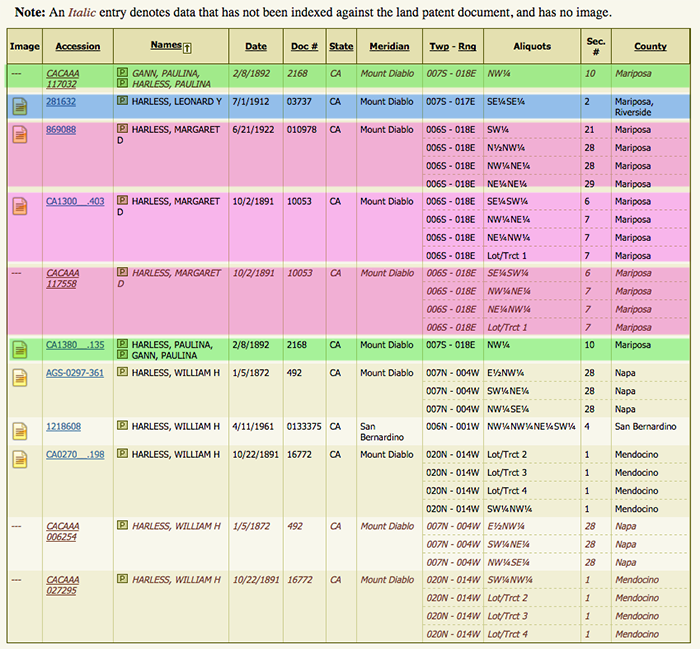

My husband’s ancestors–the Harless and Gann lines who came to California in 1858–had been ranchers and farmers, and might have acquired Homestead land. I started searching for my husband’s Harless line. Bingo! The very first entry I found listed was for my husband’s 2nd great-grandmother Pauline Adeline Gann.

The second listing for Harless on the GLO index results is for Leonard Jackson Harless himself. And since, unlike that first entry for his wife Pauline, Leonard Jackson’s entry shows that the digitized document is included, I am focusing on his Homestead claim for this post, and to learn more about GLO as well as Homestead laws.

I will definitely revisit the records for his wife Pauline and mother Margaret when I have more time. And identify William H. Harless.

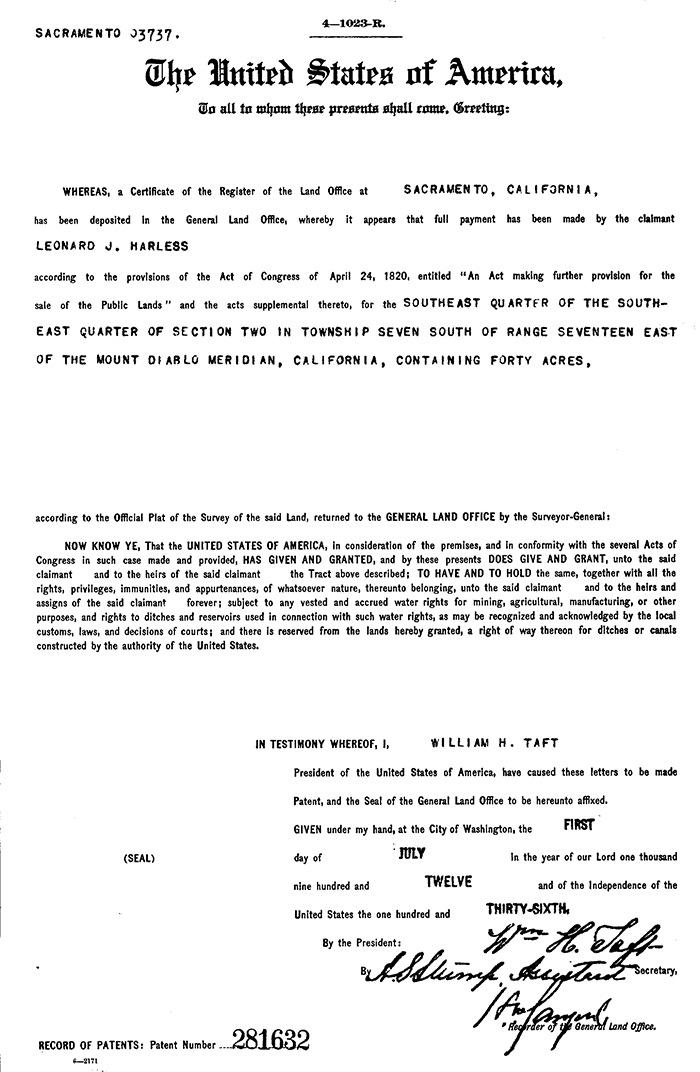

The Land Patent

I will analyze the record details more thoroughly in a later post, but following is my extracted summary, as well as a digitized copy of the original record–the serial patent file.6 I find it interesting that although Leonard Jackson grew up in a California pioneer family during 1860s and 1870s, his particular homestead patent was not purchased and registered until 1912, at 54 years of age.

- Claimant: Leonard J. Harless [index says Leonard Y. Harless]

- Registered: Sacramento, California

- Issue Date: 1 July 1912

- Issued By: President William H. Taft

- Total Acres: 40

- County/State: Mariposa County, California

- Meridian: Mount Diablo

- Township/Range: 007S – 017E

- Aliquots/Section Number: SE¼SE¼ – Section 2

- Patent Number: 281632

- Land Office: Independence

- Authority: April 24, 1820: Sale-Cash Entry (3 Stat. 566).

Here’s a look at where Leonard Jackson’s homestead of 40 acres is located in Mariposa County. I cannot wait to explore this more on Google Earth.